Episode #218: Showing Up with Miguel Cardenas

About This Episode

Miguel Cardenas takes us through a remarkable journey of transformation—from designing high-profile children's museums and nature centers at an elite architectural firm to teaching Jersey City public school students, creating powerful artwork, and co-founding the Jersey City Pride Festival with his husband Paul. This conversation explores how one person's evolution can mirror and shape a community's growth, and why showing up matters more than nostalgia.

Meet Miguel Cardenas

Miguel Cardenas is an architect, educator, artist, and co-founder of the Jersey City Pride Festival. Miguel spent 24 years as an architecture at a boutique architectural firm before transitioning to teaching construction, architecture, and art in Jersey City public schools. Through his community work and art practice, Miguel has become a vital voice in Jersey City's cultural ecosystem, advocating for visibility, belonging, and active participation in building the community we want to see.

Connect with Miguel Cardenas:

Instagram: @miguelcardenasjc

Key Insights

The journey from corporate architecture to community-engaged teaching can reconnect you to what matters most—working with local kids and sharing knowledge directly with your community

Jersey City's Pride Festival grew from a spirit of making space for everyone and a longing for local community

The "good old days" of 111 First Street aren't gone; they're happening right now at Art House, LITM, Snowball, 150 Bay, and other spaces if we simply show up

Teaching and working with students offers unexpected gifts: patience, different ways of learning, and profound connections

Architecture at its best is about narrative and storytelling, not just buildings—this principle carries through to teaching, art-making, and community organizing

Community isn't something that existed in the past—it's something we create together every time we choose to participate

Visual Documentation

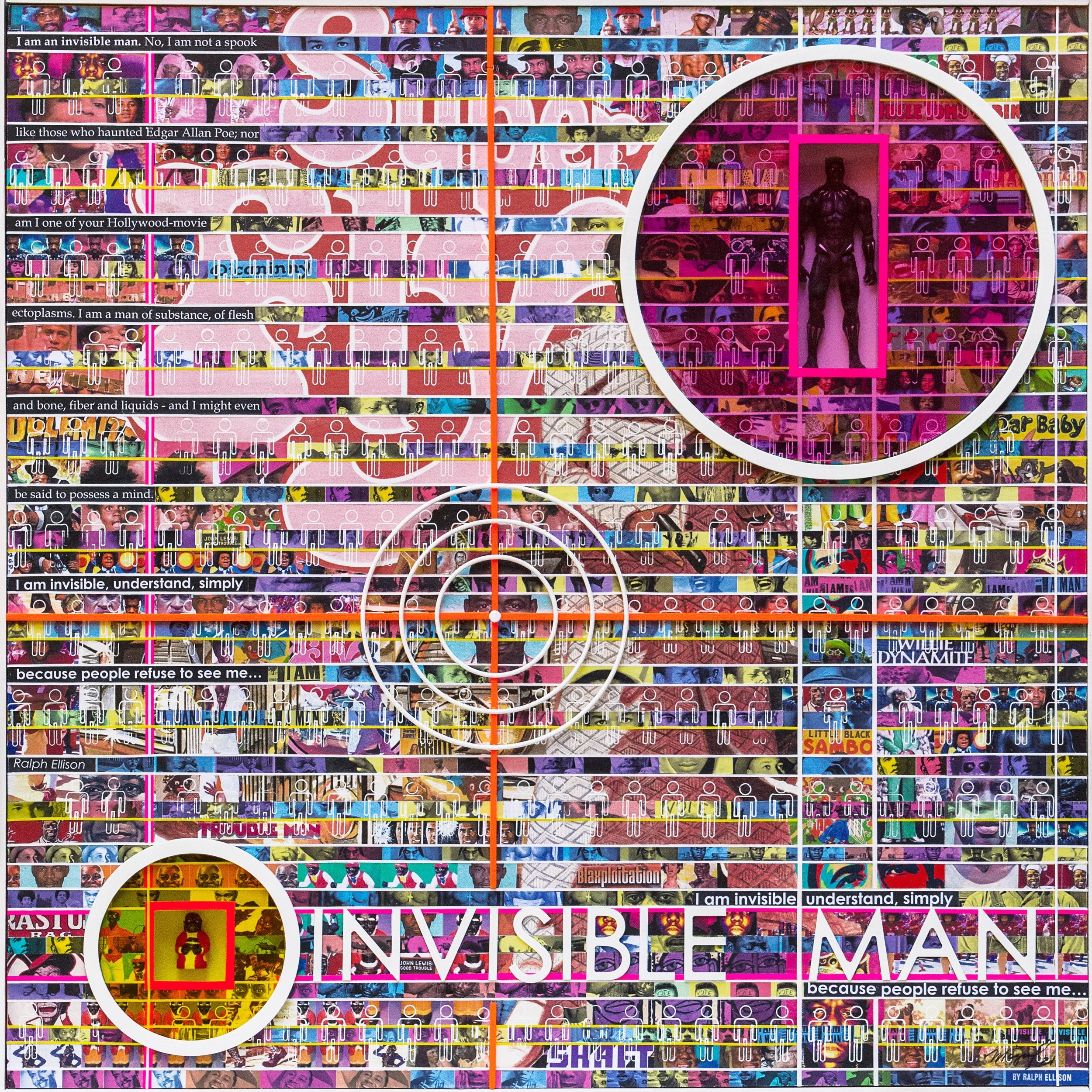

Invisible Man by Miguel Cardenas - photo courtesy of the artist

Say Gay by Miguel Cardenas - photo courtesy of the artist

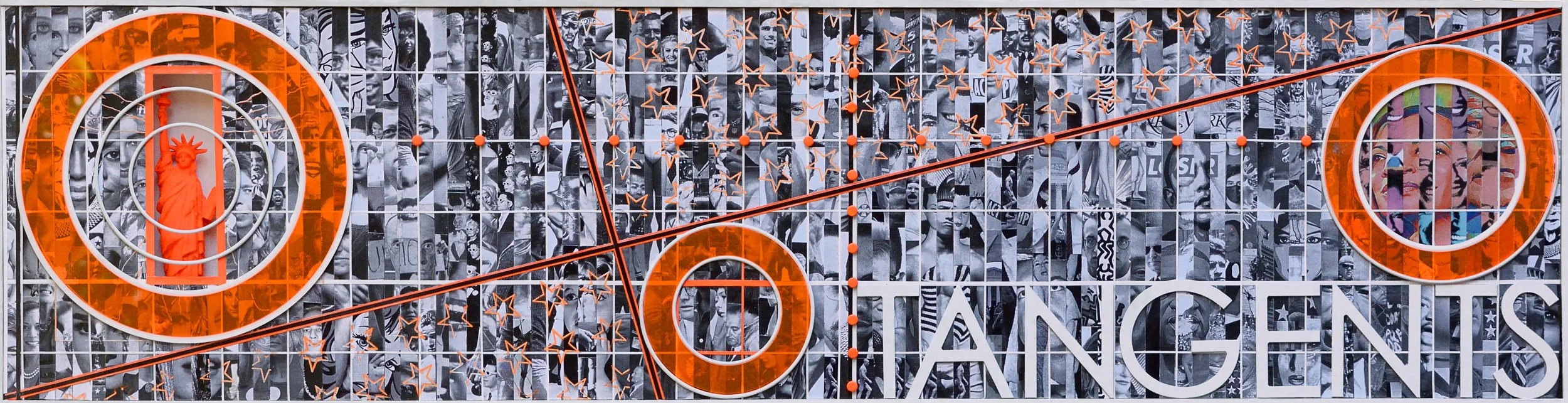

Tangents by Miguel Cardenas - photo courtesy of the artist

Utopia Dystopia by Miguel Cardenas - photo courtesy of the artist

Related Resources

Art House Productions - Currently featuring the Affordable Art Show with 130+ artists and 300+ pieces

Jersey City Pride Festival - Annual celebration drawing 20,000+ attendees

111 First Street - Historic artist warehouse and hub of Jersey City's early 2000s art scene (closed but legacy continues)

Explore Further

Coming soon on substack - an article inspired by my interview with Miguel - Subscribe so you do not miss the articles that go along with my podcast interviews.

Coming Up Next

Stay tuned for more conversations with Jersey City artists, community builders, and the people shaping our cultural landscape.

Connect with Nat

Website: natkalbach.com

Substack: https://natkalbach.substack.com/

Instagram: @natkalbach

Email: podcast@natkalbach.com

Music: Our theme music is "How You Amaze Me," composed by Jim Kalbach and performed by Jim Kalbach, Bryan Beninghove, Charlie Siegler, and Pat Van Dyke.

Support the Show: Subscribe to the podcast and sign up for my Substack to receive additional stories and visuals that complement each conversation.

Share Your Story: What sidewalk stories have you discovered in your neighborhood? Share them with me through email or social media.

Nat's Sidewalk Stories explores the intersection of place, community, and storytelling through conversations with practitioners, community leaders, and local changemakers.

Full Transcript

Nat Kalbach: Hello and Happy New Year. Welcome to Nat's Sidewalk Stories where we explore the places, people, and hidden histories that make our neighborhoods vibrant. I'm Nat Kalbach, an artist and storyteller walking these streets with you to discover the stories beneath our feet.

Today I am talking with Miguel Cardenas, an architect, educator, artist, and co-founder of the Jersey City Pride Festival. Miguel's Path is one of transformation. It's really mind blowing from co-designing children's museums and nature centers at a higher level architectural firm to teaching construction, architecture and art in Jersey City Public Schools to creating artwork that explores themes of identity and place really fascinates me about Miguel's story is how each chapter of his life connects to the next. His architectural training informs his teaching. His teaching reconnects him to community, his community work, including co-founding pride with his husband. Paul grows from a deep commitment to visibility and belonging, and through it all, art remains a constant thread. In our conversation, we explored the evolution of Jersey City's LGBTQ plus community

and the art scene, the legacy of spaces like one 11 first Street. And the quiet leaders like Joan Moore, who helped build the cultural ecosystem we have today. Miguel reminds us that the old days that people mourn aren't actually gone.

They're still happening. We just have to show up.

Hello. I'm so excited. Today I am here with miguel Cardenas. Cardenas.

Miguel Cardenas: Cardenas. Yeah.

Nat Kalbach: Yeah, that's how you say it, man.

Miguel Cardenas: You Cardenas if you were Spanish, but Cardenas is fine. I'll do

Nat Kalbach: that. So I'm super excited to have him here. I've been waiting for this interview ever since I met him. There's so many things we have to cover in my mind.

But before we do, so Miguel, will you introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about yourself?

Miguel Cardenas: Well, first of all, thank you for having me. Uh, I know it's been a little bit time coming and, and I'm glad we're here. We're here now. So my name is Miguel Cardenas.

So let's just start with like the architectural component. I am trained as an architect. I have a bachelor's of architecture, degree from Pratt Institute from way back. I graduated in 1986 at Prat, New York Was a different time back then. I worked for a couple of years in the field for a corporate firm for SOM, which is like a large skyscraper firm.

And I very quickly realized that I wanted to get more into the academics of architecture, into like, kind of like a higher level thinking. I, I love the idea of architecture much more than the practice of architecture, although I did it for 30 years. I knew that I wanted to get a master's degree, although that's not really like a requirement in my field.

It's just for people that want to go advanced into like the design world. And so there was a program at Columbia University, that was really geared to people like me, people that had a bachelor's in architecture, a five year program, and had worked in the field for a number of years and wanted to get that elevated kind of advanced design experience.

So I applied one year. I did not get in really competitive, like hundreds and hundreds of applicants and they picked like 40, you know. Wow. So the second year I tried again and I did get in. So I was very happy to do that. And it was at a great time in architecture where Deconstructivism and all this stuff was happening.

So I got in in 1990, after four years of working in the field. And it was like an amazing experience.

One of the most important, I I am still friends. It's been, you know, oh my God, 34 years now. And I just had dinner with some of them last, last week. Um, so you create these bonds with these people that are at that kind of level of thinking about this stuff. Um, and then when I got out, I realized that I did not wanna work in that kind of high corporate, world of that anymore.

So I found this firm, this boutique firm, uh, lease called architects. And I was there for 24 years. Oh wow. 24 years.

You know, I've been an architect for over 30 something years and I've only had two jobs in architecture 'cause I'm, I guess I'm a loyalist. I worked for one, one for four years, another one for 24 years.

Nat Kalbach: Nothing wrong with that either.

Miguel Cardenas: So I became their senior design associate after years of doing that. And, I was very, uh, honored and, and actually privileged to work on amazing projects.

'cause, uh, Lee Skolnick and I worked hand in hand on many very, uh, high level projects from children's museums to nature centers to really celebrity homes, which were really nice in the Hamptons to go to that. And so, you know, we had a very good clientele and a lot of repeat clients. And, and what I loved about it was that it was always about the narrative, about the storytelling of architecture.

So yeah, I was there for a while.

Um, well that brings me back to there. There's a lot of things that happen with that. Even after, after 24 years of being there, there was a moment that I was starting to get like a feeling like very, um, high, strung and overworked and, and felt I was doing my, started doing my artwork and, and we'll, we'll get to talk more about pride and, and my community work, but a lot of that was going on and I just got very overwhelmed and started feeling like maybe this is just all too much.

I felt a little bit trapped in, in being in that world where, you know, working in the architectural world, I'm, I'm not sure if, you know, it's, it's quite, uh, overwhelming and quite consuming. Mm-hmm. It, it takes over your life, you know? So I knew that it was a lot more things that I wanted to do with my life.

I felt like I had to stop that, which is a huge decision, you know, financially and just even like, what do I do now? So 2015 I decided to leave the firm,

and I wasn't quite sure what was next for me actually. And that's really scary and exciting at the same time. I knew that teaching was always a, something that I was interested in. Even in my years at Skolnik, you know, there was a lot of educational aspects to the work that we did.

Uh, from from nature centers to children's museums, always working with educators. We, we had connections with the Cooper Union, with Parsons, with different schools, and I was always the guy to be like, I'll take the kids. Like mm-hmm. You know, I'll, if there was like trips of kids coming into the office, I was always the one to, to lead like the presentation and talk about it.

And I knew that I really enjoyed that. So during that time I was like, you. Maybe the teaching thing is like what I should be doing, and I, I always had that in the back of my head. I looked into it and it's a lot harder than you think to become a high school teacher locally. I had not been in a classroom at that point, and I thought, you know, like, uh, mine and my husband's life have gotten very involved with Jersey City. I'm like, you know, maybe it's a good way to, to work with these kids that are local, you know, that, that are in our community and, and share a little bit of that.

So I applied as an assistant, uh, at Dickinson High School. I had a friend that was working human resources for the board. He said, oh my God, yes, you'd be great. So it wasn't architecture at first at all. As we had talked earlier, um, they had an opening in the special ed department at Dickinson, and I said, you know what?

That may be interesting. Let's, let's try that. And I went in there and they had just started the autism program. You know, like the kids on the Spectrum program at Dickinson. And I really had the privilege of being with those kids from like freshman year as an assistant for the four years, freshman, sophomore, junior.

Those kids still text me to this day, some of them. And they're in their twenties, you know, they're like grown. Um. And I decided to have like art shows for them. But I used to teach 'em biology and math and everything else, geology. And then there was always, and then I decided to start having an art show for them where I would spend, uh, April is Autism Awareness Month.

And I said, well, maybe we should have a show for them. And then I started inviting local people. I did that for like four or five years. Uh, and the kids got very excited about it. We even had their work exhibited at Art House and, and it was, it became a thing.

But even after the years of that, um, I started, uh, becoming very friendly with the guy who started the construction program at Dickinson. And he always said, you know, it's great what you're doing with these kids, but you could do so much more. We need you in the construction area. And he put that seed in my head, it was like the jump from being an assistant to being an actual full fledged

both: teachers. Mm-hmm.

Miguel Cardenas: I had a conversation with him.

I'm like, well, it's construction and I am not a contractor. You know, that. He's like, I know that. It's like, let's try this out. I had thought about it quite a bit actually. And you know, thinking about like, what, how can I bring the college level

academic architecture that I knew down to like a kid's level. And you know, there's other programs for other people. There's like medical mm-hmm.

both: Assistance

Miguel Cardenas: programs in high schools and stuff like that. And I'm like, wouldn't it be cool only 'cause I think there's a lot of transferable skills. Um, they don't all have to be architects, right.

You know, you learn design principles, you learn kind of just things in general, whether they wanna be fashion design, furniture design, web designers, you know, gamers, whatever. It's the same principles, right? Mm-hmm. And I tell the kids that all the time. So we started and then a curriculum had to be written and I got on that committee to write the curriculum.

And, you know, four years later, here we are. It's the first time in Jersey City District that we have an architectural design program. And, and it's just pretty much just my class actually. So it's become popular and a lot of kids wanna get in it. We have waiting lists sometimes, like, so it's, it's, it's a lot of pressure, but it's really a lot of fun.

It's a lot of fun. This is

Nat Kalbach: so cool. I find it interesting when someone once, or I, I think I myself had a problem with it when I had that burnout where I was like I have all these different interests and historic preservation in painting, uh, teaching, but also writing. Am I like weird? How is this coming together? And I actually had to, take a little moment and really sit down and realize everything is intersected and e everything fits together.

But at the first time you're like, like, what's happening here? Right. And I think for you this might be with, uh, all the things you're doing and have been doing, these are all things that are like, they're connected, right.

Miguel Cardenas: , I think that's definitely true. Sometimes you get so caught up in the day-to-day work, you know, work life, that there's just not enough time.

Right. Yeah. And I even find myself that happening now, even with the artwork, sometimes the artwork takes a back seat. I, I, when I heard Andrea talking about that, there's always that next art piece you wanna create, and I'm like, I just don't have the time for it right now. Right. Because I'm like working with the kids and I have to deal with the day-to-day stuff, even talking to you, you know what I mean?

Right. It's, there's a lot of work that is involved in the day to day where sometimes you need to take that break to just like, think

both: Exactly. And figure it out.

Miguel Cardenas: Otherwise it, you know, it just becomes not that meaningful.

Nat Kalbach: Let's pedal back for one second because I heard that you were born in Jersey City.

Miguel Cardenas: I True. I was born in Jersey City, going back to like my, my origins here, I am the first born American in my family. Uh, my parents are Cuban. They came right at the beginning of the Cuban Revolution. The whole anti communist kind of thing.

They, they fled the country. My mom was pregnant with me. She had three kids, so I was the fourth. Uh, they came in 62. I was born in 63 in January. So I was like newborn. They. Most Cubans at the time were coming to Union City. We were from Union City and I was born at Margaret Hague, the medical center, which is now the beacon.

It's interesting, I grew up in Union City as a Cuban fam, you know, Cuban, I immigrants most of my high school friends, which I'm friends with, many of them still. It was all, I grew up in a Cuban environment. They called it Havana on the Hudson at the time.

Nat Kalbach: Wow, I didn't know that.

That's so cool.

Miguel Cardenas: Yeah, everyone around me was, I ca 12 years Catholic school with, I wanna say 90% of the kids that I went to school with were Cuban. There was some Irish and there was like some Italian but, but mostly Cuban. Um, so yeah, that, that background. So I was born in Jersey City and it's interesting that I've been here now.

Oh my god, Paul and I moved here in 97. Never in a million years would I thought I would've been back.

Nat Kalbach: Can you take us back to a younger Miguel, what was Hudson County? Absolutely. Absolutely. So like, and, and for, especially for a gay man in that time, like I think that had

both: a lot to do with it.

Nat Kalbach: Yeah. What did like leaving represent, for you and, when you come back at the end of telling us, like what eventually drew you back to come to Hudson County?

Miguel Cardenas: Yeah. I came out, uh, very young. I wanna say my senior year in high school, 1981, I already knew that I was gay, you know, at that time, but it was a different time. It's not quite the same time as we are living in right now. And it was a rough time, I have to say, 'cause the excitement of coming out.

But like the anxiety of it, I just did not feel that it was gonna be plausible for me to live as a gay man in New Jersey. And I also, you know, loved the arts and loved New York City. It was an exciting time in New York. Was actually affordable to some extent to find a place to live in New York City. My first apartment in Brooklyn was $300.

Utilities included a one bedroom rent stabilized. Um, and even then I had a roommate, you know, so it was like $150 a month, I just was ready to get out and never come back. I mean, visit my parents and my family, obviously. Right. And it's close enough that, that it was easy for me to do that. So I actually went to Columbia College first and really understood that I wanted to be an architect and knew that an a architectural program would be better than having a liberal arts kind of thing.

Um. So I moved to Brooklyn at that point and, I just loved everything about Pratt, just being around the, art students as well as the architecture students, just the diversity of it all in a time in New York, which I loved. People put down the eighties in New York. I loved New York in the eighties.

It was the funnest time. I went out quite a bit. I was quite, quite the party boy at the time, but I was serious about my academics, and just living, also understanding like the, the gay life, right? And, and what that was like, the freedom that that brought to it. Um, so I'd never thought I would ever move back, but tragically my dad passed away, um, actually 34 years ago yesterday.

So I'm like very reflective about that. I'm sorry. That's always like a rough daym. Um, no, it's, it's okay. But I, I, I was just telling my siblings yesterday, we were texting and I said, you know, I pretty much separate my life before and after that day. It was tragic, you know, he took his life and it was unexpected.

Um, and. I decided to move back to Jersey to be with my mom and my sister who were young. I had just graduated from Columbia in 91, so this was 91, and I was single at the time and just starting a career and kind of in between apartments in New York, you know who it is. I was living in actually Stuyvesant Town in a, in a sublease.

And I'm like, you know what? I told my other siblings, I'm like, I think I should go back and be with mom and, and with, borrow my sister and just like, help out. Just be there for, for a year or two, whatever. So I did that. Which is weird. I never thought I would ever do that, but you know, life has its weird kind of twists and twe and turns.

Right. And along that time, shortly after that, I met Paul Mendoza, my now husband, right. It's been 30 years that we've been together. And he was living in Chelsea, and we were having like that young romance kind of thing. And then we decided after two years to move in, we looked for a place in Manhattan and Manhattan changed already.

It was getting more expensive and where I live is important to me. It's not just an apartment. I think home as an architect especially, uh, it doesn't have to be big, but it has to be special, you know? And. We looked and looked and looked in Manhattan, and it just like, he is like, oh my God, what do you want?

Like, I'm like, I want a place that feels like home, and then we had friends that were living in Jersey City, and he's like, oh my God, you guys gotta come here and check it out.

And because there's such an art scene here that's just starting up, it's affordable. You could find places. And we came in one weekend and we found a spot, and that was 1997. And we've never left, you know? We got this, great apartment in Paula's Hook at the time for $900 and. It was a walk up and you know, we still walk by it.

It was like, it was de it was before the light rail was even built. It was had even opened. Right. It was a while ago. And then we loved it. And started having people over and then slowly but surely then this is where the pride story comes in a little bit. Yeah. Um, you know, Paul is from San Francisco.

You've met Paul, my husband. Yeah. And he's like, okay, so you dragged me here from Chelsea. I'm from San Francisco. He grew up in the Castro, went to Mission High, like couple blocks away from Harvey Milk's, you know, camera shop. So that was, he's a little younger. He is four years younger than I am. So he grew up during that time, during the Harvey Milk Times in San Francisco, and he was out very young as, as as they do there.

And, um. He said, I don't wanna live in a city that doesn't have a pride. I'm like, what do you mean? Like, we have Manhattan. He's like, well, we don't live in Manhattan. We live in Jersey City. So I'm like, what are you saying? Do you wanna start a Pride festival? He is like, absolutely I do. I'm like, okay, well, you know, it's gonna change our lives, you know?

So that was 2001,

Nat Kalbach: right? And you did that with, Katherine hecht. He het.

Miguel Cardenas: I was just with her last night. Yeah. Katherine Hect. Yes. And a bunch of others. Right. Like, you know, herb, partner Beth Achenbach. Shirley after that, who's who you know and is a, a, an artist, a photographer as well from the Alley Cat.

Um, so yes, Paul, we made a bid to the city. We did all our paperwork. It was a lot of work, and we went and we were rejected.

Nat Kalbach: It was like a, it was like a grand, right? Like a slice of heaven something. It

Miguel Cardenas: was a grant called Slice of Heaven, right? And a Slice of Heaven was a program that Jersey City had, uh, for cultural groups, there was the, the Italian festival, the Puerto Rican Festival, the Irish Festival, like all of them, right?

And we said, well, we could fit in there, there could be a gay festival as part of that. And they said, no, we don't think so. At the time it was a different administration and, you know, we knew it was a stretch, to be honest with you. But we did what we could, um, and. So then when we were rejected, actually, you know Paul's very funny, he is very savvy that we're in a political way coming from San Francisco, I guess.

He said, you know what, we're gonna have to repeal this, like speak at city council. And I remember being so nervous about it. I was the, at the architectural firm and he had written a speech and there was before ChatGTP in any of that. We actually wrote stuff and I took the afternoon off. I'm like, we gotta really make the speech be like a wow speech in some way.

Right? And we got our voices out there. We had already been having meetings. We started an organization called Jersey City Lesbian and Gay Outreach, JCL Go, as many people know it back in the day. And so we had our little group of people starting community. Mm-hmm. And it wasn't just about the Pride Festival, it was a really about creating community.

Mm-hmm. The Pride Festival was one aspect of it that we really felt was important to take it off. But it was just about having the, we saw people that were, you know, we thought and we knew were L-G-B-T-Q mm-hmm. In the neighborhood. And we said, wouldn't it be great living here for us not to have to go to Manhattan and have this world in this really cool place that we're living in?

And so we. He spoke and gave this amazing speech at City Hall, and we called the press.

And the next day in the, in the jersey you got standing ovations

Nat Kalbach: too, right?

Miguel Cardenas: Yes, yes, yes. No funds for gays in Jersey City was on the front page. Timothy McVay had just been convicted. It was like the se second thing, and that changed everything.

It was an election year. We knew that. We knew that it was election year and elections for mayor in Jersey City back then was in June. The new mayor that was coming in, Glen Cunningham. We prayed down to like, you know, who we lost, but Glenn and Sandy, his wife would later become a, a state senator.

Became, he became the mayor. And, you know, she was his wife at the time. She wasn't quite a senator yet. And it changed everything. He's like, no, we're gonna have it. I'm like, what? Which is

Nat Kalbach: so amazing. Like, I wanted to ask about that. Within a month

Miguel Cardenas: It changed. It changed in a month. Yeah.

Nat Kalbach: So I wanted to ask you about that because, um, you are the guest before you, Jerome China.

He's a sculptor. He is a great artist. Um, you know, at the end of the podcast I will ask you my signature question and, he answered who he would love to meet from the past with Glenn Cunningham because he would love to talk with him about what Glenn would think about the city.

What became out of it, but also because he was n not able to actually implement a lot of his, plan. So how was that for you to have the first black mayor of, uh, Jersey City actually support pride in that way?

Miguel Cardenas: It, it was wild. So it changed everything. And like to us, just someone, who was like a straight military guy, you know what I mean? Like, you know, not comfortable at all with the whole LGBT thing. But he understood, and I think Sandy, his wife had a lot to do with it.

So we'll never forget it. She speaks to this in the documentary a little bit actually, right? It was the morning of like August 24th, 2001, and Paul and I are like running around not knowing what to do. You know, like just besides ourself, like, oh my God, like this is happening. This is crazy.

Like putting tents up and everything that everyone, we didn't know what to expect and of course, we invited them to speak. And they showed up very early, like way too early. And Paul and I were busy and we're like, oh my God, I'll, and I'll never forget, she was wearing like a floppy hat.

It was like in August morning it was really hot. And we're like, I'm like, Paul, the mayor and his wife are here. He wanted to go there and see what this thing was gonna be about. 'cause he was nervous about it. Like, I'm supporting this thing and like, I'm just a, a new mayor and what's it gonna be like?

So we ran to them and we're like, oh my God, welcome. Thanks for being a little early, but fine, you're here now. And then, like, we very quickly became very comfortable and walked them through like the whole site and explained what the whole day, what we were hoping the day to be like. You know, it was our first time so we didn't really know what to expect, but they were so welcoming and sweet, and just like embraced us in so many ways.

Um. So quickly, and, and we knew that we could almost feel that there was an apprehension on their side. 'Cause there just, there was no precedent for it in Jersey City, but you know, sure enough that that day was the most wonderful day ever. Right. Like, you know, for Paul and I like, we'll never forget that day.

Like it changed our lives. It really, really, really changed our lives forever. Um, it's amazing. And

Nat Kalbach: you changed the life of so many other people as well. Right. And you said in the beginning that this was, also about community for you. How do you feel like this as an institution here, those are like

Miguel Cardenas: outflows from, from our side.

Yeah. Like, I mean,

Nat Kalbach: like that's the beginning of it, right?

Miguel Cardenas: It, it really was. And it was funny 'cause I didn't think that that was like a big deal. But for Paul, it was. He felt, he, I mean he still feels that every city in the world should have Pride festival. And I just thought like, no, I'm New York was fine.

I had fun in New York. It was great. And then I wasn't, I was always like a spectator. I was never part of running it. And it's a very different point of view when you're there having fun versus actually running it and doing that sort of thing. But, community, honestly, like that group of people that we're still, we just had an event for one of our friends that's moving away, he's moving to California last night at Pint.

And we were all there, you know, 25 years later, like the crew was there saying goodbye to this person. We are like a family, honestly. And my own biological family knows a lot of those guys because they used to come and support us early on. It's been 25 years, a long time we've grown together.

Yeah. We were like youngsters back then. So it is interesting, um, how that happens, but what's even more important, which I wanted to like make the bridge to the art was, you know. 2001 still, uh, was very different than the time that we're living in now.

It was pre-marriage equality. Don't ask, don't tell. We're still in there. And, you know, AIDS unfortunately was still a big part of our lives, and, you know, I'm HIV positive living with that and, and fine, I'm very healthy. But it was a different time. We were still losing a lot of people back then.

Mm-hmm. And there was a focus on that. And sometimes I felt like. Not that there's never too much of a focus, but I wanted to bring a little bit more joy or expand that community aspect of it. And that's where, where Paul was pushing like the pride and the politics of it. Paul's very political and, and he always felt that pride is, is not just a party, it's like a political event.

And, and I support that as well. And we've taught people that have come after us. Mm-hmm.

both: That,

Miguel Cardenas: So then I had this idea and I said, well, why don't we just for a moment, like I was dying to be an artist and I hadn't done the artwork.

I had done artwork related to my architecture, but not as a, it took me years before I could call myself an artist. I used to say, I'm an architect playing an artist, and I said, what if? And I spoke to Kat Hecht and, and at that point, Beth Achenbach and Paul and, and the other people that the leaders, I said, what if for our tour, we would have an L-G-B-T-Q show?

I will curate it. I will put it together. We'll ask local L-G-B-T-Q people, we'll do it at our house at Paul and I's apartment and Paul is hooked. Right? And that was another life changer really. So in 2002, like a year later, we decided our, our mission statement was, we are a vital voice in Jersey City.

Committed to bringing the L-G-B-T-Q community together. That was our mission statement. So Vital Voice became a very important, I love the alliteration of that. So I, I started the Vital Voice Show

both: Mm. For the

Miguel Cardenas: City Art and Studio tour in 2002. And we did that for 10 years. The first three years was in our house, and I have to tell you that weekend.

So it became like Pride Weekend became Paul's weekend and I helped him. And then my weekend was the art tour and that became almost as big as pride in, in a different way, in a much more personal, kind of informal way. But people came to our house that never left our lives since then, honestly. Wow. Like we would start.

On the Saturday morning, sometimes Friday night, I put up the show in our house, cleared the furniture. We had a, an incredible spread. Sometimes my mom would cook stuff, we would have a lot of liquor and a lot of art, and a lot of conversation. And we just opened up our house till these people that we just didn't even know who they were half the time.

And some of them never left our lives, honestly. And we've had so many great memories of that. Right. And, and you know, um, the, the woman who started LITM came in before LITM and introduced ourselves, uh, Jolene, uh, Jolene came into our house as this Filipino woman and he was like, oh, you're a Filipino to Paul.

And she's like, I wanna start this bar called LITM. I'm like, you know, it, it's interesting how you make these connections and then. LITM becomes like a huge part of our lives after that. Right. Christine Goodman, who is like a dear friend and will be forever connected because art house started the same year, that pride started.

So we're fledgling organizations that, we'll, we'll always have that bond forever. Mm-hmm. Art House and Pride, uh, and they speak about it and we speak about it and we've been very supportive of each other throughout the years. But those weekends, and we did that for a long time, uh, of the Vital Voice Show was like a big deal.

And some artists to this day said, you know, I would've never done art if I hadn't shown there. Wow. It was much more than the, the quality of the art. It was just a community. Yeah. Hung out. And it was fun.

Nat Kalbach: In both things that you have done you have given your community a safe space to be who they are. Right? Like one is like the being at the Pride Festival, you can come out and be who you are with other like-minded people and allies and be supported by the city too.

That makes you feel safe too. But then also in the house where you have artists, you, you can show your art and be safe and be who you are. So I think there's like a, a huge connection in what you're doing.

Miguel Cardenas: Even on a personal basis, even like my family's always been very supportive. Um, I'm one of six and my siblings and their kids and my nieces and nephews grew up around that and they would be there as well.

So it wasn't just like a completely all LGTBQ. Yeah. And I had a lot of straight friends in my architectural world that came.

So it was like very open in that sense of like. Also seeing it from the other side for them to see, oh, shoot. Like, these guys are like, just like us. They're hanging out.

They're like, you know, having a good time. And, well, it's hard to imagine

Nat Kalbach: that there, were there. Well, it's not hard to imagine. We know where we are living in this time right now, which is very, uh, difficult again. But I'm thinking like, I was born in, you know, 73, I lived in Germany and I, my, my mom has always had, friends from the lgbtq plus community.

I just grew up with that as like there wasn't a question. And then being in a city like Hamburg.

I would go to Pride Festival with friends so it wasn't even like a question for me really anymore. So now thinking back, like thinking back at the eighties, but also what you're saying about Jersey City and not having pride and all that, that, it's so interesting to me because I, when I moved to Jersey City in 2013 and I saw that there's a Pride Festival, there wasn't even like a question for me that that must have been around for longer than it has.

Right.

Miguel Cardenas: My nieces and nephews that are now like in their late twenties and thirties. Have been coming to pride every, every year. And like, so they don't know a life without having, you know, they just came as little kids and saw the drag queens and so everybody else hung out there and wore the T-shirts and like, all that kind of stuff.

So it's, we still have niece and nephew night here at home sometimes, like where they come in and they, you know, they come and talk about their parents and , Paul and I are like, you know, okay, the

Nat Kalbach: cool uncles.

Miguel Cardenas: Yeah, exactly. Whatever they, uh, but because they talk back at, you know, those days that when they were like five, they came to pride.

You know what I mean? It's, it's kind of, it's very sweet and very supportive. So yeah. That, that art thing happened to the point that it got so big in our house that this, this brings us back to community, which is interesting. Yeah. You know, pint of course, right?

Yeah. Pint are right. Yeah. And so there was, before it was called Pint, it was called the Star Bar. And the owners of Star Bar that came to like Pride, I'm like, you know, it's getting to be too much for it to be in our house. You know what I mean? We were renters in an apartment.

And they said, they, I'm like, oh my God, that they're gonna open a gay bar in Jersey City. But they hadn't gotten their certificate of occupancy yet for Pride. Like we had worked on it. And then, so I talked to Eric Blair and Dermot, like these two guys that owned the Star Bar, it was called before It was Pint.

And I said, what if we have like the, the art show there? He's like, well, we're not ready yet, but if you guys supply the liquor we could just make it like a party kind of thing. And so we did it that year. We moved from our house to what is Now Pint, which back then was called Star Bar.

Everyone, everyone thought that Paul and I had opened a gay bar in Jersey City.

The night before, like literally the paint was still wet on the bar to the point that people got like their clothes dirty because the, the stain on the bar was still wet. Paul and I were cleaning, my mom had cooked some food, like Cuban food or whatever, like, and we had it all, and they're like, oh my God, finally you guys, and those, all those walls were filled with, with LGBT artwork.

It became like an establishment.

both: Amazing.

Nat Kalbach: So cool. That would be like a documentary in and itself too, like another one. Let's talk a little bit about your art too, because you're always so generous to talk about other people's art, but I wanna talk about your art too, because it is amazing.

It's stunning. I'm gonna put some in the show notes. Your art draws heavily on archite nic, um, spatial concepts, right?

Miguel Cardenas: It's funny, it's like you can get away from it and, and just like these last couple of weeks teaching the kids design principles, you know?

Yeah. From balance to repetition to rhythm and movement and alignment and all those kinds of things. I know that most fine artists probably don't think about those as much, but me as an architect is the crossover between art and design. Right. And a lot of people don't understand the differences.

But I live in that interstitial space between art and design, I think, where I do apply a lot of design principles, and I, and I tell the kids, they're like a bag of tricks. You know, like you have a, as an architect, we can get away from the grid. I use grids quite a bit. Like it's part of our nature.

And then as much as I try to break it, I find myself not going back to it all the time. I make sure that there's like something, a bit of emphasis at some point, and I do apply those principles. And so I do use that as an organizing element.

For the work, but the, the actual work itself is really based on this idea of, of this interstitial space or this in-between zone. Mm-hmm. Between binary oppositions, which I think, you know, male and female, American dream and, and a dream that's lost. Catholicism and the sacred and the profane and like those kinds of things finding that Venn diagram where things kind of, you know, mix up and where, and I say where things are not either, uh, not either or, but both. And, and I use that a bit. Which is part of like the post-structural thought, postmodern thought that, that I learned at Columbia.

You know what I mean? Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. It was like that was what deconstructivism is about, right? When you really start thinking about critical theory and that sort of thing. So it comes from that and I learned it and, and you know, collage work for me was something that I learned in Catholic school. Like back in the seventies and like late sixties, it was really big and hip to be to do collage or, so I always chose, do a book report or do a collage.

I'm like, I'll do the collage, you know? You know, and I love like iconic imagery, like, and I talk about a collective memory quite a bit, . And my work is somewhat nostalgic in a lot of ways. I work with a lot of iconic nostalgic images. That in memories, especially people, whether it be pop culture or art history, or just history in general and, and, and kind of mix that to, to get messages across of the present.

So I, I don't want to think that my work is nostalgic in the sense of looking back at a different time. It's using images that are part of our collective memory, whether it be, , through advertising or just those ideas that we remember. Mm-hmm. Celebrity, you know, not, you know, I borrow a lot from Warhol, obviously, and b Rauschenberg and all my heroes, you know, uh, Jasper Johns and the rest of 'em.

I love art history. I have a minor in art history, like art, art since 1945, actually, very specifically. Uh, and so I try to bring that all in. I do have a pretty amazing like, uh, photographic memory in terms of remembering things of like these images that I grew up with or, you know, I used Farrah Fawcett quite a bit and to try to bring like a different story into that. You know, my use of Farrah Fawcett she was the woman that changed equal pay for women in Hollywood. Do you know that? No,

Nat Kalbach: I

Miguel Cardenas: did not. Wow. So it's always about that, before the, the whole transgender talk, I, my, one of my, I used to do shadow boxes, one of my first shadow boxes mm-hmm was called he, she, and it dealt with we all have that femaleness and the maleness and each of us and, and that what is that crossover between, you know, male and female?

I used to do a lot of digital work and now I've kind of gone back to like, hand cut with an exacto blade and gluing down. 'cause I. I find it more gratifying for myself. And I also think we're living in a very AI world of art where it's become, like it used to, it would take me 30, 40 hours to do one of those digital pieces.

And now people, you know, don't appreciate it as much because they just like go on AI and say, oh, you know, type in whatever and get it. So I find it that the, the one of a kind hand cut pieces mm-hmm. Which I find so gratifying and zen like to do it, but they take me forever.

Yeah. They take 50, 60, 70 hours at a time, you know, to, so

Nat Kalbach: the little like, like when you put, you also put sometimes like little figures in there. Right.

Miguel Cardenas: And that's my architectural background. They, they're like, they're, those are architectural figures that are made for models for scale.

Yeah. And I just put them in there. So it's a lot of found object stuff. I don't really. Make a lot of this stuff. I think my work, my art is mostly based on that, the concepts of, like, that, that, yeah, I, I do manipulate images quite a bit with color and oversaturate them and deal with that kind of thing.

But it's really the, the research part of it is my favorite part. When I come up with an idea and then I start creating these folders and I, I'll spend. Hours and hours and hours and hours. Yeah. Like creating, I have, I have this amazing library of images, um, depending any subject that you can imagine.

Nat Kalbach: How do you store all that? Do you have like a, like a whole

Miguel Cardenas: computer

Nat Kalbach: somewhere?

Miguel Cardenas: No, no. Honestly, I just like put 'em on thumb drives and stuff, you know what I mean? Like, and then I have folders and folders and folders of like these cutout printouts of like whatever subject matter. So I do good gift wrapping because it's like I have those images in it.

Like I just wrap stuff up for very specific to the person I'm giving them too. Oh, I love

Nat Kalbach: that.

I love your work. It's, it's really amazing. I need time with it because it draws you in right away and you, and you react to it, but then you know that there's so much more to see and to uncode, I don't know if that's the right word in English, actually. Decoded. It's decoded.

Miguel Cardenas: I understand what you're saying. And, and I think you got it. I think, uh, it's like candy sometimes, like mm-hmm. You look at my work and sometimes I, I know that it, it's a know, it's a trick, the bright colors, like the images that I use that people know, it draws people in, you know?

That's part of like the, the gimmick part of it. Right. To draw you in right off the top. And then it's not what you first thought it was. 'cause sometimes that candy is like poison candy. Exactly. And look at it closer, like, oh shoot, like this is like pretty serious stuff here. Like images of war and suffering Right.

And injustice and social injustice and that sort of thing. And, and I do that almost kind of, that's part of that, that Venn diagram, right. Of like what seems pretty on the, um, you know mm-hmm. They're very pleasing to look at, like, you know mm-hmm. I think because of those things. But then they're very disturbing.

both: Mm.

Miguel Cardenas: Many of them are when you look up close, right? Yeah. And you're like, well, there's something really pleasant about looking at this thing. I, I wouldn't mind having it over my couch. But then again, like, do I want, which is sometimes a problem, uh, with selling the work because they're like, I love it, but I don't know that I want it in my house.

Because it's like, it could be like somewhat the political aspects of it. I mean, not always, but

both: Yeah.

Miguel Cardenas: You know what I mean?

Nat Kalbach: You didn't study on top, graphic design, right? Like, how did you No, I didn't.

Miguel Cardenas: I didn't, I never That you just like learned that

Nat Kalbach: by yourself,

Miguel Cardenas: I guess. You know, and I also, you know, also during pride, I, I was like the creative director of Pride, like communications in general.

But I think it's part of, like, I, I tell the kids now when I teach 'em, like design is, design is design, whether it's graphics or architectural design, it's the same principles apply to all of it, right? Mm-hmm. And when you design a building or an apartment, it's about, mm-hmm. It's gotta have some narrative of storytelling.

As a basis, then you have to have design principles, and then it's gotta work. You gotta get your message across and it's gotta be functional and aesthetically pleasing. Yeah, yeah. All those things. I, I really like test myself. Like is it aesthetically pleasing? Is it, does it carry a message? Is it a meaning?

Does it keep people engaged? You know, like, oh, that, otherwise it's not worth it. Yeah. It's

Nat Kalbach: interesting because I used to teach, art classes for adults and, um, I've taught a lot about design principles too, and you think it's just in you, but when I think about it, I do think about visual triangles and rhythm and all these things.

Some people might do it more intuitively and they wouldn't be able to really, um, verbalize that, but Exactly. If you know

Miguel Cardenas: it well enough, then you could break it.

You gotta know this stuff to the point that it isn't conscious. Right? It's like driving a car. When you start driving a car, they tell you, present the brake, you know, present the accelerator. And when you start driving now after like 20 years of driving, you don't think about all that stuff.

You just do it, right?

both: Mm-hmm.

Nat Kalbach: It's a really cool, I totally get that. As you're talking about your students, I would love to know what do you learn from your students? They learn from you, but what do you, did you or what do you learn from your students?

Miguel Cardenas: Well, that's a great question. 'cause so much, first of all, first, first and foremost so much 'cause we get so carried away with the content stuff that we're trying to teach and sometimes you realize these kids like need, um, there that is important and you get that across, .

But what I've learned from them is like so many times, um, I. They just need to be guided in some way, right. Or listened to, or be seen in some way. Right. And not just be talked to, but be understood and understand where they come from and understand that, some of them may not be having the greatest day for many reasons.

Sometimes I may pull them aside and ask them what's going on or what's not. You know, a mentor, a friend, a mm-hmm. Counselor, like that sort of thing, that is a big part of the job more than you think. Mm-hmm. There may be days that I have like the lesson perfectly down and I'm like, okay, I am ready to go.

And then you could just see in someone's face like, oh my God, like there's something going on here and what is that? Right? And that is our job as , sometimes I come home like very excited. I'll talk to Paul. I'm like, I can't believe what this kid just talked to me about.

Mm-hmm. You know, like they're, they're coming up with concepts right now for this project, this little ninth square grade project just this morning, this kid. Who was like new to the school and, and it's loving the class. He's doing great. And he's like, I, I, Mr. C, like they, they'll call him Mr. CI have an, I think I have an idea.

I think I have an idea. I'm like, you have an idea. Like already. Well that's cool. 'cause you just like, he's new. I. He's very bright. He's like, I think my thing is gonna be just from hearing you talk about the big idea and the concept and all that. He showed me the little diagram that he is drawing, like all, you know, abstract, you know, not, and he's like, I think it's gonna be about like, you know how like poor people have like all these worries all the time and then rich people have like all.

Free time and like, how do I make that into an architectural project? I'm like, dude, like,

both: whoa, this

Miguel Cardenas: is like really heavy, like, kind of stuff, right? I'm like, oh my God. Like that gr brings me into like ideas of like, you know, red lining and, and you know, and I'm like, you know, reason why, you know, highways and stuff and the edges living on the other side of the tracks, you know?

Have you ever heard that? And some people Yeah. Heard that and I'm like, where does that come from? Living on the other? So it's amazing how someone could just open it up. And that became the lesson today. Like, I'm like, let's look that up, living on the other side of the track as an architectural concept, right?

And sure enough, people have dealt with that and so I, it, it makes me teach 'em. Like, what do you think? Like, you know that the Jersey Turnpike mm-hmm. Divides Dickinson, upper Hill, lower Hill, and. Downtown wasn't always wealthy. 'cause when I was growing up, downtown was pretty, uh, you know, not the safest place in the seventies, but honestly, back in the 17 hundreds and 18 hundreds, it really was.

You know what I mean? And that was the outskirts. So you had these edges to towns and it's like a whole, so it's amazing how sometimes they could bring something up

both: mm-hmm.

Miguel Cardenas: That could lead to something else that you just didn't think that they would have the capacity to even mm-hmm. Think. Right?

They're kids, but they're human beings. And honestly, like, you gotta listen. And be perceptive. Then you're the adult in the room and like, you know, sometimes, so, and then sometimes they just teach me about myself. They, they'll laugh, you know?

You gotta have a sense of humor. Yeah. They'll tell me like, you know, like noone one wears like, you know, pants like that anymore. I'm like, shut up. Like, what do you know about fashion? But they do know, 'cause I watched them, you know, like, and I'm like, I learned from them a little.

I'm like, well that's pretty cool. Like what you're wearing there right now.

Dickinson as a whole, and because they are lower income, it's really, I, I realized that, you know, I came from a privileged place in going to private school, even though we weren't wealthy, but we had parents that were very caring for us back in the seventies and eighties.

And some of, most of these parents are as well. They're just working their butts off to just get these kids. Mm-hmm. A lot of them are really new to the country. Mm-hmm. Like new, like some of them like arrived like, you know, within the year, you know, so language is an issue sometimes. I'm so proud of the kids that I had last year that didn't speak a word of English.

They only spoke Spanish and now they're fluent in English. You know, I'm like, oh my God, like, I can't believe you're speaking to me in English. And so there's a lot of hope there, but also to expand them, to think of them like that. You are enough and you are capable of doing this.

And you know, honestly, because they see me as a, a weird anomaly. Like, and I'm like, I was just like you. Mm-hmm. My parents didn't speak English. You know, I was first generation immigrant. I did not know how to speak English when I was in kindergarten and first grade. I did not, you know, and I learned it as I went along and, yes.

I sound really in your mind, very eloquent. And I went to Columbia and all that stuff, and they see me as like a rich white guy.

both: Yeah.

Miguel Cardenas: It's like I'm light skinned and, and sometimes. When I start speaking in Spanish and my Cuban Spanish to them, especially the Latin ones, they're like, oh, shoot. Like he's, I'm like, I hung out on a stoop, just like you did in Union City.

Like, right.

both: I,

Miguel Cardenas: you know, like, I was just like that. I'm not like the superhero, you know what I mean? Like, if I did it, you can do it, kind of thing, you know? Yeah. But frustrating that, I think a lot of them just don't even think that it's possible.

both: Mm.

Nat Kalbach: My last question, I would have a hundred more, but I'm conscious about you also and time, but, um, if you could spend an afternoon with anyone from Jersey City's past, who would it be? Which corner would you choose as your meeting spot and what one question would you ask them?

Miguel Cardenas: I don't know if you know this person, but this person, uh, meant the world to both myself and to Paul back when we started Pride. And her name was Joan Moore. Do you know who Joan Moore is?

I don't know how long you've been in Jersey City. No. Joan Moore was this woman who worked for cultural affairs in Jersey City for over a decade. She died in 2008 of cancer. Unfortunately, she was an African American lesbian woman, but that's not even the main issue. But she was, and it's important to the story because she was in charge of the slice of heaven. Program that I was talking about or not in charge, she was the one that ran and put those festivals together. If you needed to put a festival together, you had to go to Joan Moore. Right. And Paul and I went to her with the Pride Festival. And really the smile on that woman's face when we showed up and told her what we wanted to do is, it's almost like, and I think she did tell us, like, I don't wanna like put words in her mouth as someone that's not around anymore.

But it's almost like I've been waiting for you guys like to, to, for someone to come and, and, and do this. Right. So this woman supported us in ways that you couldn't even imagine. And even, you know, at first it's, it's not like she said I'm a lesbian. I mean like, yeah. But, whatever. We had our feelings about it.

We kind of thought that would be possible, but along the way she was just there for us every step of the way to make sure that it did happen. Right. Or to make sure that we didn't get discouraged. 'cause the book she gave us of like the forms and you gotta go to this department and that department.

You gotta get these approvals and that is street closures and then you gotta go to city council and you gotta, , it, it's overwhelming, honestly. Like, it's almost like we should have just run out, not ever come back, but she's like, no, but we can do this. We, we will work through it and we will get it together and.

So that same woman was fighting a lot for one 11, and you've heard a lot, I think in your podcast of one 11, this amazing art space, right. That is now this stupid empty lot mm-hmm. That nothing was ever built. She also was fighting hard for that. Right. So, to keep that open and, and thought like that if one 11 died as a place that what the art scene in Jersey City would've died as well, and which a lot of us thought that would be the case.

We visited one 11 a lot. Paul and I, at that time, we thought it was the coolest freaking fun place on earth. Uh, but I remember during the art tour when we were doing that at our house, and she, she was a busy woman. She was running part of the art, the Jersey City art tour as well at the time.

So we had this intersection between the arts, that art tour and pride, and then she. Such a humble, you know, I learned a lot like Paul and I used to say like, it's incredible. Like she's so quiet and unassuming. And I'll never forget this one story. And I reminded Paul about it last night, how we were at Victory Hall. There's the big party, right? The opening night for art tour. Mm-hmm. And back then they've changed through the years. That used to be a amazing night. Everyone here, the art community and everyone showed up at these things. It was the, one of the funnest nights before snowball,

before all that. And here it was at Victory Hall, on Grand Street, right? Like, and we lived right there and it is winding down. And we lived down the block at Paula's Hook and Joan is sitting there like outside, she's like getting older. By herself as the big party's going upstairs.

And I'm like, Joan, like, what are you doing out here? Like, what's going on? She's like, I'm waiting for a cab. I you gotta get home. Like, she's getting older. She was like, probably like a little sick at the time as well. And I'm like, what? Like you are waiting for a cab like that party like, and I'm like, I'm gonna go home and get the car and take you home.

Like, and we drove her home that night. I'm like, this woman, who is like the creator of this, a big part of the creation of this whole thing is sitting quietly out here and just like that. I'll never forget that. So yes, it would be Joan Moore, because honestly, like, she went to, she died in 2008, so she lived through like at least seven of our, um, of our festivals and saw them grow through like the years and was always very happy and supportive, but also like, because of the art scene,

one 11 is gone. And I know that the old timers are like, you know, we'll, forever mourning and you know mm-hmm. Tris McCall wrote that beautiful piece on the Starship and all that. Right. Um, but we're still here. Right. And it's still like living and, you know, LITM came by and Art House is, is doing a great job and so is a lot of other, you know, uh, 14 c, what would you ask her Bay?

So I, I think I would meet her at the Grove Street Station there. 'cause back then

both: mm-hmm.

Miguel Cardenas: Newark Avenue was not what it is right now. Newark Avenue had an ordinance that you had to close at midnight, and Paul actually spoke at City Hall for LITM to stay open till 2:00 AM because we loved L-I-T-M-L-I-T-M was the only game in, in town at the time.

But just to stand there at that corner on Pride Morning.

When the March is coming through and saying like, Joan, could you imagine like that, you know, we had a thousand people the first time, which is great for the first time, but we have 20,000 people coming to Pride right now. Right with a march and that same spot, you know, like even for the art tour, she would have her little tent for the art tour at the Grove St station.

Right. And giving out the maps, and the t-shirts. So like, that's that hub of that corner. And just being at that corner and just tell her like, you know, so what do you think?

Yeah. So for pride or for like the art scene, like, you know, what, what are your thoughts? Did you, could you ever even imagine this? Or do you think that it, we did something wrong? I don't know, like whatever. Just, you know what I mean? She just didn't get to experience it, you know? Yeah. Like 2008 was so early on and she was a little sick and it's unfortunate that we lost her.

'cause I think she had like a lot more to give.

Nat Kalbach: What a wonderful, what a wonderful pick. Thank you so much for introducing her to me and probably to, um, some of the listeners or maybe some will know her. So that's a, that's a great pick. This was such a wonderful conversation.

Do you have anything art-wise that's coming up in the, near future?

Miguel Cardenas: Right now, the Affordable Art Show at Art House, so I always do cathedral arts, affordable art show. I create work in the summer. Uh, and then once in a while I'll, I'll have a show, so I don't have one planned just yet, but I think everyone should go.

Honestly, like, I can't believe it. 130 artists and over 300 pieces, like God bless Andrea McKenna for like, putting that show together. 'cause to hang that is like, I, I couldn't even imagine.

We were just talking about one 11 and people keep saying, I wish I, we had those art days back. You know, those of us that are still here, they, they still occur. Show up. You just have to show up. Right? You gotta show up to snowball, show up to art house opening, show up to one 50 Bay Pro Arts, all of them, you know, every single one of those places because you know, we're there, I'm there, you know you're there.

I see you

both: there.

Miguel Cardenas: Right? Like at at at those, the, the art crawls and all them. Because if we don't show up, who will? Right. You know, like no many people do actually, but we, it's just fun to like have not lose that community. And so I do get annoyed when, when even artists themselves say, oh, remember those old days?

I'm like, you know, those old days are still happening. You just,

Nat Kalbach: I like that you say that because I, I agree that it is sad to hear about one 11 first Street, but it's also, there's a lot of things happening. In the art, art scene in Jersey City, there is a lot of artists. There are a lot of galleries. There are a lot of spaces, and yeah, it can always be better too.

Of course, of course there are things that are not working so well, but, um, it is actually quite amazing. But I do hope that, we will get to see, a show of yours, soon again. So check out Miguel's, uh, work. I will link everything up in the show notes and post some of his artwork as well. Follow him on Instagram.

And thank you. Thank you so much for this. Wonderful. Well, thank you so wonderful

Miguel Cardenas: much. This has been a pleasure.

Nat Kalbach: Wow. Thank you, Miguel, for this journey through your many transformations and for helping us understand how Jersey City's Pride Festival and arts community grew together, often supported by the same people, and the same spirit of making space for everyone. Your choice to meet Joan Moore at Grove Street Station on Pride Morning is so fitting, imagining her at that corner where she once handed out art tour maps. Now watching 20,000 people celebrate Pride reminds us how one person's quiet determination can help transform a city. And your call to show up to Art House, to snowball to the gallery openings and art crawls really speaks to the heart of what this podcast is about.

Community isn't just something that existed in the past. It's really something we create together every time we choose to participate. Thank you for that reminder. All links to connect with Miguel and see artwork can be found in my show notes along with information about the affordable Art show at Arthouse Productions.

Make sure to subscribe to my Substack, where you'll find a new article inspired by this conversation next week. Until next time. Look up. Look around, and remember the vibrant community you're looking for might be happening right now. You just have to show up. Thank you for listening to Nat's Sidewalk Stories.

I'm your host, Nat Kalbach. Our theme music is How You Amaze Me, composed by Jim Kalbach and performed by Jim Kalbach Bryan Benninghove Charlie Siegler and Pat Van Dyke.